Three Fragments

September 29, 2023

I’ve been trying to write a long form essay since my last one about Gong Gong Gong back at the beginning of August. We’re closing in on two months. I’ve started writing about a handful of topics. Two of those topics inspired me to write 7000 words before I realized there was no way I could turn them into something coherent. I gave myself a deadline of the last day of September, which is tomorrow. I don’t think I can change anything around on what I’ve written, but I figure I can salvage the parts that were important to me, and give them to you, devoid of any context. I order I give them to you is not how they would have appeared in the final essay. There would have been many paragraphs of “glue” between these. Perhaps they would have been pulled apart and put back together in a form hardly recognizable. I’m out of time though, so this is the form they have to enter to the world.

Starting today, I’m going to try to enforce a regular update schedule for myself. On the very last day of every month, I’ll have a new essay on here. What is an essay? I’m not sure, but I can give you a vague idea. My essays are different from my journal entries or my snapshots. Those are more free. I write something and it’s over. I don’t think very deeply. My essays, however, require me to psychoanalyze myself for multiple weeks. I produce thoughts I’d never had before, but those thoughts are agonizing to produce. I suspect they might be pretty agonizing to read as well, or at least exhausting -- but I have to hope that some people like agony and exhaustion.

To put it simply, essays are pieces of writing I can fail at in ways the rest of the writing on this website can’t.

The following is what it looks like when I fail.

Contents:Why her? Obviously it was the album art for Beat Pop: Koizumi Kyoko Super Session. She’s leaning over, farting like it’s a super power, as clocks from a surrealist painting attack her with their tentacle-like power cords. One hears the name “Beat-pop” and wonders what it could possibly mean in the context of 80s J-pop. Whatever you imagined it as, it’s probably not what you actually hear when you put the album on and the first track Cutey Beauty Beat Pop starts playing. Country Anthem Rock guitars mix with sci-fi Hip-Hop breakdowns. Koizumi (whom fans affectionately refer to has Kyon-Kyon) sings inscrutable-to-me lyrics about “knife and fork folk rock” with a kind of feminine accent only someone who has devoted their life to the study of the kinds of cute and terrifying second-hand objects they use as decorations at Lolita fashion stores could hope to replicate. Then suddenly Downtown Boy starts and there’s this crazy synthesized bass line battering its way out of the machine that created it, going completely out of control — the kind of sound one imagines could be found in video games, only to spend a life time of disappointment failing to find anything approaching that electronic violence.

“So this is ‘Beat-pop,’” I whispered to myself, alone in my sister’s room, after she’d left the United States and gone to New Zealand. I’d moved into my mom’s house in order to commandeer her room, and for the first time in a year I was sleeping in a bed.

By the time Heart of the Hills came on, a coldness filled my heart, matched by cold air from outside that my sister’s thick quilt was slowly thawing out of me.

Beat-pop has more traditional idol pop songs on it. Listen to Good Morning Call, for instance. It has enough idol magic to satisfy anyone. But where a more typical idol album puts in filler for the remaining half an hour of the album, Beat-pop inserts labyrinthine monstrosities of production.

Hiromi Ohta’s album Tamatebako was one of the first genuine Showa idol pop albums I’d downloaded. It is a masterpiece. It’s unfortunate that it took me almost two years to actually listen to it.

I found her on Soulseek, in 2017. I was looking for Sasara’s album 上京娘. When I typed “ささら” into Soulseek’s search bar, the only result was a single person hosting Tamatebako. It turned out there was a song on there of the same name. So, as I always do when I hit a dead end on Soulseek, I downloaded whatever mystery I happened to find at that dead end. I listened to Sasara, the song, and found it uninteresting. I didn't bother with the album again in the Spring of 2019, after I'd already fallen deep into Kyoko Koizumi.

Tamatebako, it turns out, is fascinating, a dark world of electronics completely different from, say, Akina Nakamori’s. Put in the context of her older music, it's even more mysterious. Songs like よそ見してると feel like continuations of her 70s sound, with vague hints of folk rock inside a J-pop framework, except we all have a fetish for strange electronic sounds now. It is the exception. Most of the album shows zero continuity with the past, outside of her shrill voice. It's not that her earlier music was "normal". Songs like 葉桜のハイウェイ on her previous album I Do, You Do had backing tracks like something from a Bomberman OST. Tamatebako felt like it took everything a step beyond that. This is the J-Pop dream. Every song a new world, and you are the Dreamin’ Rider. (Momoko Kikuchi is someone else I've listened to extensively, yet I'd be hard pressed to write anything meaningful about her).

I feel like I have to make up stories about how far back my relationship with this music goes. I’m 26 now. 2019 was 4 years ago. It’s not deep history. My time with this music feels so significant though. I wish I did have a deep history with it. I wish I had encyclopedic knowledge of it. I wish I was more than a guy who just downloaded a bunch of files or clicked on a bunch of Youtube links.

The only reason I continue to think about Kawamoto as much as I do is that she happened to be the background music of a quite short but distinctive period of my life.

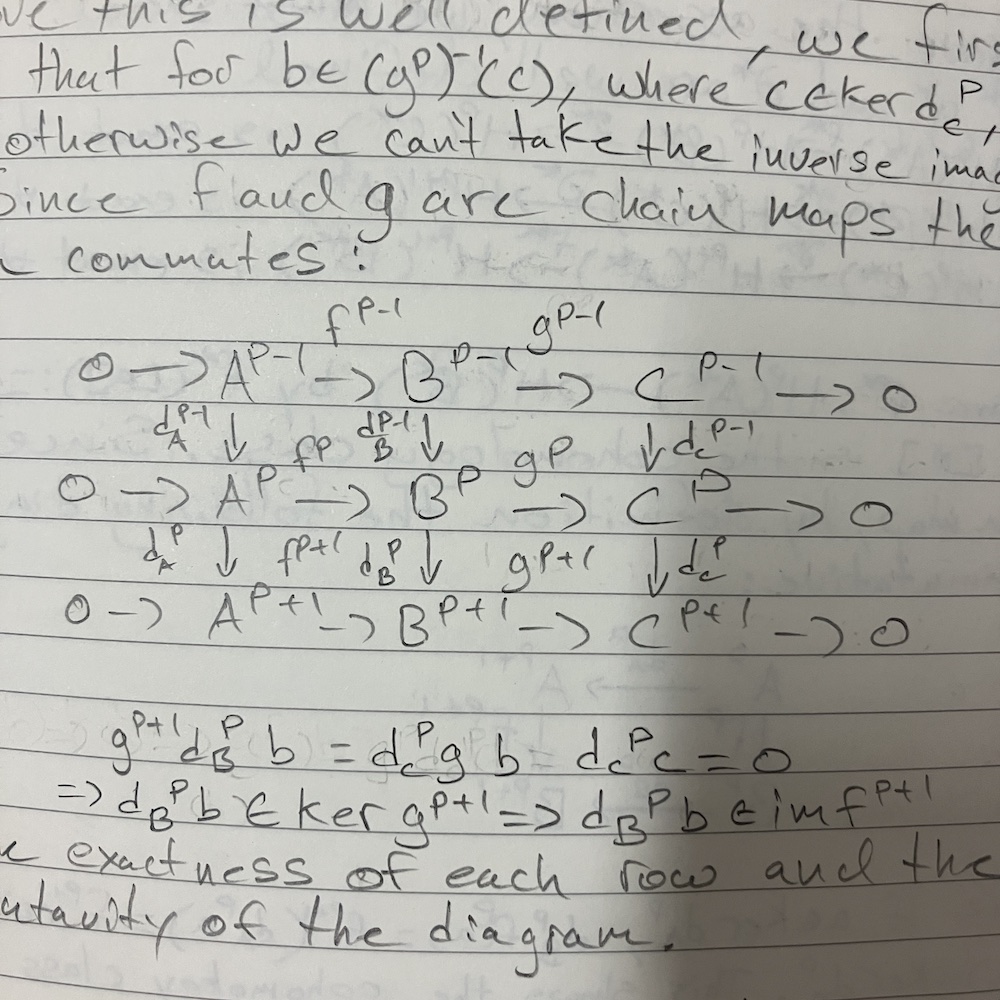

The week I was working on my Smooth Manifolds Year-End Homework, I listened to Makoto Kawamoto with Goronyans and New Friends constantly, with brief interludes of Happy End. The core of the homework was De Rham Cohomology, as was the core of the class. Cohomology was quite a surprise for me, taking that class. I’d had a vague idea of what a manifold was before the class: some multidimensional curved shape. I even knew the actual definition: near any point a manifold looks like Euclidean space (in two dimensions that’s the usual xy-axis everyone is familiar with from middle and high school). So I had a pretty good idea what the first few weeks of class would be: we’d define manifolds, give some examples and talk about their basic properties. The next step in the course, tangent spaces, was completely natural: of course we’d need something that generalizes the derivatives of curves we know so well from calculus, since how else are we going to think about the “curvature” of manifolds? The additional abstraction via fibre bundles used to introduce the Tangent bundle wasn’t particularly surprising either. It also made complete sense that you could give the Tangent bundle a manifold structure.

But I had no idea what the more advanced content surrounding manifolds would be — the kind of stuff one would encounter a month or two into the course. It definitely never occurred to me that the most important idea in manifold theory would be cohomology. It was especially baffling to me because my Chinese was terrible for the first semester, so I didn’t really understand intuitive explanations, only equations and technical “math-speak” (which is easier to understand than more conversational Chinese, since it’s just direct translations of English words (or the same German and French words that English math words are a direct translation of)). So suddenly we went from thinking about spheres and other geometric shapes, to looking at mesh like charts of “Chain complexes”. I understood the definitions and the theorems, but I had no idea why we were doing any of this, which is what made it so fascinating to me. It felt like I was looking on the other dark side of geometry. To each geometric object, we discovered it had some other nature as a mysterious chain of algebraic objects that can’t be visualized. My year end homework involved long in-depth calculations of those algebraic objects.

I should mention that this was right when China’s zero-Covid policy had ended. Everyone was sick except for me. I went to the completely empty library every day and spent 8 hours a day on the year end homework. The Tongji library consists of two giant cubes tilting out of a central cylinder. The two cubes house the books and reading rooms, while the cylinder is just has a hallway for each floor. Wooden tables on a marble mosaic floor line the walls. You can stare out the window at skyscrapers against the overcast sky (Shanghai is overcast at least four days a week, often quite more. It’s fantastic. As a wise man once said, The Sun is my Enemy. I’d love to live in a place like Chengdu where you might go a whole month without seeing the sun.)

During the summer the windows are often open. A warm breeze mixes with the cold air coming out of the air conditioning. During the winter the whole place is freezing. I have to wear my jacket indoors.

When had I got to China everyone wore masks outdoors, but immediately took them off indoors, which seems like the opposite of whatever best practices are supposed to be. The introductory graduate classes for the math department had about 70 people in a room, and no one wore masks. Once the pandemic “ended” classes all went online. The stance of the government seemed to be that everyone will get Covid, and the sooner the better. My school on the other hand encouraged anyone who could go home to do so. Campus was deserted of almost everyone other than international students. It was such a wonderful feeling. I realized this is what I’d been dreaming of all along. When the pandemic started in America I’d completely locked myself down. For the first two months I didn’t leave the house once because I didn’t have any masks, and because my mom appointed herself as the grocery purchaser, since she had to go to work still anyway. By the time I acquired masks, it was May, cases were down quite a bit in Maryland, and there were already people filling the streets everywhere I went.

So it was only late December in Shanghai that I got to selfishly experience that Covid freedom. The world had become mine. It didn’t really seem like I could get sick, since my roommate hadn’t infected me. (I’d already gotten Covid (for the very first time) back in August.)

All the convenience stores near my dorm were closed due to staffing shortages, so I had to walk 15 minutes any time I wanted to buy something. I enjoyed that. I don’t like things to be too easy. If there’s an easy way out, I take it every time, but I hate myself as I’m doing.

As December turned into January the city became even more deserted. Those who weren’t infected with Covid had gone back home for Chinese New Year. For a brief period time it was just me, Makoto Kawamoto, and De Rham Cohomology.

Without any intuitive knowledge of what cohomology actually is, just manipulating these objects using formal rules and theorems, I got a 94/100 on the homework. The day after I turned it in I went to my girlfriend Xiaoxi’s office at 11pm so that she could take me to her house and we could go to the hotsprings the next day.

I now know that Cohomology essentially is the main tool that lets us look at how manifolds look at a “macroscopic” level, rather than just near a point. A natural way to classify different manifolds is by whether or not we can “stretch” one into the shape of another without “tearing” it. So a sphere is fundamentally different from a donut, because a donut has a hole in it, while a sphere doesn’t. To give a sphere a hole you’d have to tear it, which isn’t allowed. (Maybe this "rule" seems arbitrary. Ultimately it, like all other definitions in mathematics, is arbitrary. The theory it produces, however, is useful and interesting.)

Therefore, to understand the shape of manifolds, holes are important. What homology and cohomology do is they give us information about the “multi-dimensional” holes of a manifold, most fundamentally how many holes there are in each dimension. That’s where the chain comes from: we have a different algebraic object for each dimension, and they’re connected by a “boundary” mapping that relates holes with their boundaries. (I’m conflating Singular homology and De Rham cohomology here, but for manifolds they give the same information.)

There was something depressing about slowly realizing how simple cohomology actually is. It seemed so immensely complicated when I first saw it — and in it’s modern form with all the different frameworks and abstractions built around it (e.g. derived categories), it is extremely complicated — but the idea itself is so disappointingly simple.

All through my adventures with cohomology, I was hearing Makoto Kawamoto’s voice from a land somewhere between the sunshine of acoustic guitars and the purplish-darkness of drum machines and synthesizers. Were we in the 90s or 2023? Kawamoto’s 2016 and 2019 albums were neither. Was it language or sound? Again, neither. Just as the geometry of manifolds somehow found a dark algebraic side, so did this music. I imagined many armed bodyless ball-like creatures hanging from a dangling ever-crumbling framework growing out of every note of this music. If only it could be frozen in time I’d be able to take a good look at it and actually understand it, but it’s creation and destruction was too fast, moving past me at every moment, so all I could do was stare at the ever accumulating descriptions of De Rham cohomology I was writing in my notebook.

If I’m going to write about my experience with Showa Idol pop at any length, I’m going to have to bring up former author of long articles about video games, and current director of long documentaries about video games, Tim Rogers. I tried to think of a few ways to naturally transition into talking about him, but ultimately there is no natural way.

I want to bring him up because his essay A Cartoon Androgyne Between Two Fashionable Imps is what prompted my “second go” at Japanese music, when I was 17. I actually didn’t get into idols because of him. I got into rock music.

Up until then I’d listened to Shibuya-Kei and a handful of other older stuff, like Jun Togawa. When I started reading his essays, they were filled with references to Number Girl, Yura Yura Teikoku, Boredoms and Boris. These were extremely well known Japanese rock bands. If I’d had any curiosity about Japanese rock, I’d have found them sooner or later. After two years or so of listening to older “smart” pop music (ultimately culminating in me discovering Seiko Oomori, which put me on the cusp of becoming a fan of the modern alternative idol), he put me back on the path towards rock ’n’ roll.

I was vaguely aware that he had a deep appreciation for Showa idols. However, even when he wrote about it directly in the above mentioned essay, it was vague enough that I didn’t retain anything from it. (The very first Japanese names he mentions in that piece is Kyoko Koizumi’s! Yet when I found her music years later on Soulseek, I wanted to scream out “How did no one tell me about this?”) He never talked about the way Idol pop made him feel, the way he would describing Number Girl or Sambomaster.

Any time he’d brought up this girly music elsewhere, he talked about it only through the lens of artistic achievement. This isn’t just Tim. This is the vast majority of English language writing (and Chinese language writing) I’ve seen about old J-pop. There’s at most a tacit allusion to the sugary sweet melodies of the Showa idol having a deep connection with the other forms of music that you'd expect a grown up vessel of male teenage angst redirected towards deepcut-audiophillic obsession would enjoy (e.g. YMO). City-pop is described as real art. It’s easy to connect it with Jazz fusion, American RnB, and modern underground DJ culture. The synthesizers and elaborate intros of Showa Idols is real art too, at least in so far as it can be sampled. But what about the most generic girly voices layered on top of the most generic girly chord progression, arranged in the most generically girly way for the most generically girly orchestra? What if that’s what I like? I’ve found over and over that I don’t really have the mental tools to coherently describe what that makes me feel.

To make matters worse, talking about anything more than a single song is a minefield of contradictions, since it’s not like idol pop is any one sound. Every singer worked in many different “genres” (or one might say pastiches of genres). These genres range from Samba to Disco, House to Jazz. Though often they were mutated into new, unrecognizable forms. In the 70s, both The Candies and Momoe Yamaguchi sang songs orchestrated with a sort of post-Rock ’n Roll brassiness, though even then the similarities are superficialities. Where the Candies did preserve a certain kind of sweetness and girlishness as they evolved, by the end of Momoe Yamaguchi’s career, her music exudes a darkness and grittiness about as intense as would have been possible for a female teenage pop idol in the 70s. Sometimes she was actual Rock n’ Roll. Other times she was a voice echoing from the shadows.

There’s another reason I have to bring up Tim Rogers.

An astute reader summarized my essay Descent as describing me “trying to live [my] brother's life, and being unable to do so.” This is of course a completely accurate summary of the essay (and it’s where the name “descent” comes from), though I hadn’t actually conceptualized it that way. Maybe I simply have "the little brother personality."

I read Wang Xiaobo’s novel 2015 when I was 17. The narrator, a physicist turned novelist, tells the story of his uncle Wang Er (literally “Wang number two”), an artist who keeps getting arrested for selling paintings without a permit. His paintings are strange and vomit inducing, but they make girls horny. They also make police officers very angry. They beat Wang Er up, take his money, and use it to buy ice cream for more serious offenders like burglars, who at least have a little heart. The narrator describes this as the circle of life, the way things are supposed to be: artists make art, they get arrested and beaten up, then their nephew comes to pick them up from the police station and they immediately start making art again. The narrator similarly follows his uncle around, hiding under tables to watch his uncle hand his paintings over to his Japanese distributor, only for his uncle to see him (Wang Er has orbital hypertelorism, which gives him a wider field of vision than most people), and start yelling at him. It doesn’t matter. Wang Er keeps selling paintings, and his nephew keeps stalking him.

Everything goes out of whack when the authorities decide Wang Er’s been arrested too many times. They send him to a reeducation camp where he gets chained to a desk, and electrocuted until his hair falls out. After failing to learn a skill more socially useful than painting psychedelic squirrel-tail-like spirals, he gets sent to the alkaline fields. The police officer in charge of supervising him falls in love with him and takes him back to Beijing so she can force him to have sex with her at gunpoint.

All throughout this sequence of events, Wang Er’s nephew is quite dismayed. First Wang Er is hated too much, being sent to the reeducation camp, and then he’s loved too much by “police officer auntie.” He’s supposed to be quietly loathed, quietly punished, and quietly released. Nothing more and nothing less.

I suppose I’m a lot like Wang Er’s nephew. Once people start liking "my uncle" too much, I get angry. He's supposed to be hated.

Of course it doesn’t seem likely that many people would want someone like me as a nephew. I’d be quite a nuisance.

There’s all sorts of psychoanalyzing one could do to determine why I ended up like this. For instance, I never really saw my dad as someone to look up to as a kid. For one, he was bald, and I wanted to have long luxuriously flowing hair. My brother was older than me enough, and his appearances were infrequent enough, that he could function something like the archetypal cool uncle. though unlike the typical sitcom uncle, my brother wasn’t nice to me. He was mean, like Wang Er. I still found it mildly pleasant to be called a retard.

When I first encountered Tim Rogers’ writing, he didn't really have a "community". He had a Twitter account. He had less than 4000 followers. If you ever ran into people on the internet who were talking about him, it was almost always negative. People who hadn't read his articles would make fun of him -- so if you did read his articles and you saw how much depth there was to them, it was very easy to feel like his only fan in the whole world.

The fact that Tim felt unknown and hated made imitating his style feel more natural. For the first creative writing class I took in college, I handed in a 15,000 word novella I'd written in a single 12 hour sitting that was basically a parody of Tim Rogers. My professor was astounded. She brought up the possibility of getting it published. She told me “No matter what, you can't stop writing. The world needs your voice." It made me feel horrible. I felt like I'd gotten away with plagiarism. In the strict sense of the word I hadn't. The plot of the story was nothing like Tim Rogers had written and it's not like I actually copied any of his sentences -- though I'd taken elements from his biography and personality to create the characters. The central conflict was that the main character is sterile, but his wife was somehow pregnant. She claimed it could only be his baby, and she accused him of running away from responsibility by stating that he's sterile. For whatever reason the protagonist refuses to actually get tested at a hospital. Instead he goes on some adventure to figure out who the father is. This protagonist processed the world through metaphors derived from Japanese rock. In any conversation, there was a decent chance he’d bring up BOOWY’s Bach-Chorale like melodies or the head-splitting guitars of Number Girl.

This is all to say that even as I have consciously tried to go in other directions with my writing, so many of the mental tools I have for writing and thinking about music come from Tim. Before him, I’d read a bunch of modernist poetry. I’d read Ezra Pound’s ABC of Reading, which demands its reader work through thousands of years of the canon in its original language before even hoping to understand modern poetry. I read the modern cultural critics on Twitter or in magazines like the New Yorker, talking about whatever the 2013 equivalent of Barbenheimer was (I’ve long since forgotten). Tim’s writing was neither of those things. It felt like a way out. It felt like a way to talk about the modern world, modern life, the modern predicament, outside of “the western canon” (replacing it with a 20th Century Japanese canon), and without saying the same dumb stuff everyone else on the internet was saying.

10 years have past, and every day I’m dealing with how useless that Tim-derived toolbox is for writing what I want to write about. Maybe this is what I get for hardly taking any humanities classes in college. If your musical taste is assembled entirely out of what you can find at thrift stores, if someone happened to donate 100 CDs of Power Electronics the day before you walked in, then that becomes the prism that you listen to all other music through.

I want to write about music my way. I don't want a canon -- Western, Japanese, or Chinese. Can't I just read books and listen to music outside of any feeling that what I'm spending time with is "artistically important"? On some days it feels necessary, on other days it doesn't even seem possible.