Too Scared to Think Big

Aug 17, 2024

I’ve been flipping through The Whole Earth Catalog (which I’ll abbreviate to WEC below) the past few days, and it’s been evoking all sorts of strange emotions in me. I’d been aware of the catalog for years, but I’d never actually read it before. After I got home from two weeks in Beijing and Jinan, I was in the mood for book recommendations. I suddenly remembered WEC, which I was vaguely aware of as the ultimate source for a lot of second hand recommendations I’ve received over the course of my life.

To save me the work of describing it, here is what Wikipedia has to say:

The Whole Earth Catalog (WEC) was an American counterculture magazine and product catalog published by Stewart Brand several times a year between 1968 and 1972, and occasionally thereafter, until 1998.

The magazine featured essays and articles, but was primarily focused on product reviews. The editorial focus was on self-sufficiency, ecology, alternative education, "do it yourself" (DIY), and holism, and featured the slogan "access to tools". While WEC listed and reviewed a wide range of products (clothing, books, tools, machines, seeds, etc.), it did not sell any of the products directly. Instead, the vendor's contact information was listed alongside the item and its review. This is why, while not a regularly published periodical, numerous editions and updates were required to keep price and availability information up to date.

If you’re a computer person, specifically the kind of person who cares about “the history of computing” more than the actual modern incarnation of the personal computer, then there’s a good chance you’ve encountered WEC discussed as an influence on people like Steve Jobs or Alan Kay. A lot of these histories love to pontificate on the mythology of the hippie to computer entrepreneur pipeline, and WEC is often positioned at the center of that pipeline.

It’s all a bit strange, since the catalog itself doesn’t have very much to do with computers. It’s, on the whole, a lot more concerned with tipis and nomadics than computers. Why should technology be the only context in which it’s ever brought up?

From the outside, programming culture can seem quite strange in its expansionist tendencies. Everything uses computers these days, so programmers feel like all of human knowledge lies in their domain. I too once lived a life where I considered myself a programmer (though admittedly, only a programmer of video games), so I can appreciate this culture of intellectual colonialism.

Programming itself isn’t all that deep, yet it has a lot of applications. It presents as good a framework as any to learn about all sorts of things: linguistics, mathematics, atmospheric physics, art, music, and so on. Many of its practitioners consider programming to be a sort of craft, so it inherits a lot from other older (masculine) crafts, like woodworking, automobile maintenance and hobbyist electronics — the kinds of crafts one could read about in the books listed in WEC. I think this culture led me to being a lot more diverse in my reading habits than I am now. I was always convinced that I could study anything and it would somehow be useful for programming or designing video games.

At some point I gradually started to think of myself as an "artist" — or at least I fantasized of being an artist. It’s almost certainly true that a lot of the best artists are similarly "interested in everything". However, when I started overhearing the kinds of conversations that arts people have, I felt completely behind all of them. All of their touchstones were different from mine. This transition happened in my early 20s, but I already felt like I was coming to art at an advanced age, and therefore I felt like I had to find a way to catch up with them. This feeling is responsible in part at least, for the narrowing in scope of what I read. I generally only read literature or books related to literature in some way. I don't get sucked down weird rabbit hole hobbies the way I used to.

When I wanted to be a game designer/programmer, I was convinced every side-hobby would eventually contribute to my craft. So mathematics for instance started out as a side-hobby that I ended up pursuing a little bit too deeply. A lot of what makes mathematics enticing to a normal person is rather elementary geometry, number theory, and applications to other fields like physics. Yet one of my problems is I always tried to pursue each of my side-hobbies "the right way", which was usually defined not by other hobbyists, but by professionals. So when I studied mathematics, I used fairly heavy duty textbooks that were meant to prepare one for abstract modern mathematics and which alluded to topology, category theory and so on. I kept feeling like I needed to study these relatively advanced topics. Things got out of hand, and now I'm a mathematics graduate student.

My study of Chinese was similar. It started out as a hobby, but I felt like if I didn't study the great literature from throughout the ages, much of which is written in several different versions of a literary language fairly removed from modern Mandarin, then my study of Chinese would be a waste. So I've spent many many hours trying to read Classical Chinese, far more than "an ordinary student of Chinese", and yet I can't compare to actual specialists, Chinese and foreign, who devote their lives to this literature.

I want to go back to the old days, when it felt like I could start up any hobby/craft/interest I wanted and it would prove valuable somehow. I'm scared though that I'll once more fall into another multi-thousand hour abyss that just furthers my sense of isolation.

As a specialist, it's nice to feel like you know more than anyone else about something, but you eventually learn how much of a burden knowledge can be. The kind of mathematics I've studied is useless outside the context of proving theorems and writing papers at the frontiers of modern Algebraic Geometry. I've been pushed past a lot of the foundations of the field, the more concrete examples that Algebraic Geometry originally sprung out of. As such, I feel a bit rootless. I'm always behind though. I don't have time to study 19th century geometry or number theory. To keep existing in this world of modern mathematics, I have to keep swimming even deeper and deeper into modernity without looking back. Maybe if I didn't spend so much time pretending to be an artist, I would have more spare time for mathematical recreations, and I wouldn't have this sense of perpetual unease.

Writing this, I can't help but recall the story at the beginning of Zhuangzi about the massive bird Peng, which, due to its extreme scale, must be supported by thousands of miles of winds and oceans in order to fly anywhere. The tiny sparrows laugh at it, being content to fly from tree to tree without consequence. In some ways, devoting oneself to theoretical mathematics or ancient Chinese literature both feel like quite free and easy occupations, being rather useless arts removed from the concerns of the world (like the tree that Zhuangzi praises as a source of shade to lie beneath, yet which his arch nemesis Huizi decries as a big and useless (just like Zhuangzi's philosophy...)), but somehow I've approached them all wrong and turned them into a cage locked in a prison cell.

Returning to WEC itself, its self-identification as a set of tools makes me think of Neocities, where every other website has a “resources” page. And yet I wish Neocities "resources” pages were a bit more like WEC. Everyone here seems relatively narrow in their scope (which is understandable -- my website isn't particularly broad in its subject matter either). What I typically find is just links to HTML/Javascript tutorials and maybe a few tools for generating graphics. 9 times out of 10, “resources” just means “resources for making a Neocities site”.

One gets the sense that the goals WEC hopes you’ll aspire towards are slightly more ambitious than a personal website. The most obvious theme running through the catalog is the commune: so many of these books are devoted to the kinds of practical problems one would encounter trying to form a self-sufficient community out at the edge of civilization. This, of course, is an extremely difficult problem that few have succeeded at tackling. Despite that, I suspect the vast majority of people who read the catalog back in the 60s had no plans themselves to start a commune. Such a difficult problem as starting a new society instead serves both as a guide to finding smaller meaningful problems to solve, and as a measure against which to put the solutions to said problems in perspective. For a book on a particular craft, for instance, printing, to be useful to a commune that, say, wants to publish a weekly newspaper, it would need to be practical enough in its scope that it explains how to get started with minimal materials and knowledge. Such a book would also be quite useful for a whole number of other people who have no plans of dropping out of society but, say, just want to print an underground magazine (no small feat in itself). A book designed for professional printers who just want to be up to date on the state-of-the-art techniques of their industry wouldn’t be all that helpful for either hypothetical audiences. Yet you also have very fringe books on subjects like people inventing languages or whatever, because again, maybe a new society will need a new language. This commune/individualist undercurrent of the catalogue therefore elevates its scope to embrace all sorts of knowledge, knowledge big and small, knowledge from the “whole of earth” — even if it’s true that dissecting this latent ideology would probably unearth a lot politics that seems questionable to the kind of person writing on Neocities in the year 2024.

At the same time, many of the reviews in the catalog evoke a nauseous reaction in me, regardless of the product itself under review. Inside these pages, one finds a prototype of a lot of the sorts of thinking I remember encountering on Quora back in 2015.

When I talk to people in real life, I always get the sense that I’m the only person whose had their run in with internet infinite scroll addiction on, of all places, Quora, the pretentious intellectual version of Yahoo Answers, rather than the more normal platforms like Twitter, Instagram or Tiktok. I imagine most of my readers are at least vaguely aware of Quora, as its initial corporate strategy of ad-lessness and monetary rewards to people who write high quality answers meant that, for a time, it often showed up in Google results. But at some point the company had to make back all the early investor dollars they’d burned on growth, which seems to have resulted in a massive reduction of quality. That said, even in the golden age of Quora, there were all sorts of questionable intellectual currents flooding the site. It was populated by a certain sort of techno-sage that might have a lot of real knowledge about one particular topic, but has also read a single book each on a dozen other areas that they claim expertise in.

The intellectualism of the site meant that there were a lot of questions about “deep” topics like mathematics, however these were typically asked and answered not by people whose main focus was math, but by programmers and finance-type people who liked to imagine themselves as “good at math.” Math got reduced down to a sort of olympiad problem view of math — which is very different from the world I discovered after I spent a few years studying math seriously. When “math people” did talk about math, it felt like they were just name-dropping legendary textbooks like Rudin, giving the impression that it’s only through a small handful of classic texts that one can learn mathematics. (I personally think a lot of these famous 60s textbooks suck.)

Similarly, the people asking and answering questions about literature weren’t people who actually loved literature, but instead tech people with slight literary inclinations. These were people who had a handful of novels they liked, but tended not to read super widely. A lot of the recommendations of books and assessments of authors ended up boiling down to the same cliches or to weird idiosyncratic claims that got voted upwards because they seemed novel and were stated with bravado — not because they were correct in any way.

I think more than anything else, there was a lot of telephone going on: people repeated distorted opinions they’d seen other people state, and eventually it just became a fact that, say, Soviet textbooks were all hardcore and scary (like Landau), and American textbooks are warm and gentle (like Feynman). Once I actually studied mathematics, I discovered all sorts of extremely friend Soviet textbooks, ranging from the introductory textbook series by Aleksandrov, Kolmogorov, and Lavrent’ev, to more advanced texts like Shafarevich's book on Algebraic Geometry, which is a thousand times friendlier than the book by Hartshorne — an American (though, admittedly, a Shakuhachi playing American with a massive beard).

There's nothing wrong in having a casual interest in a bunch of things — it’s just the demographics of the website and the way the ranking system worked tended to result in questions and answers that seemed deep and profound, but not actually coming from a place of knowledge, simply because they were written by people smart people who aren’t actually all that familiar with the topic at hand, but good at constructing answers that seem intelligent to other people unfamiliar with the topic. When there were good answers written by experts, those did tend to stand out and get voted to the top — the problem was that for most questions, there weren’t expert answers. What worsened this was that Quora questions were asked by Quora users, immersed in Quora culture and all its strange views on mathematics and self-learning. This in turn encouraged more fake-deep Quora-style answers — creating a whole culture of confusion plastered over with the illusion of grand wisdom.

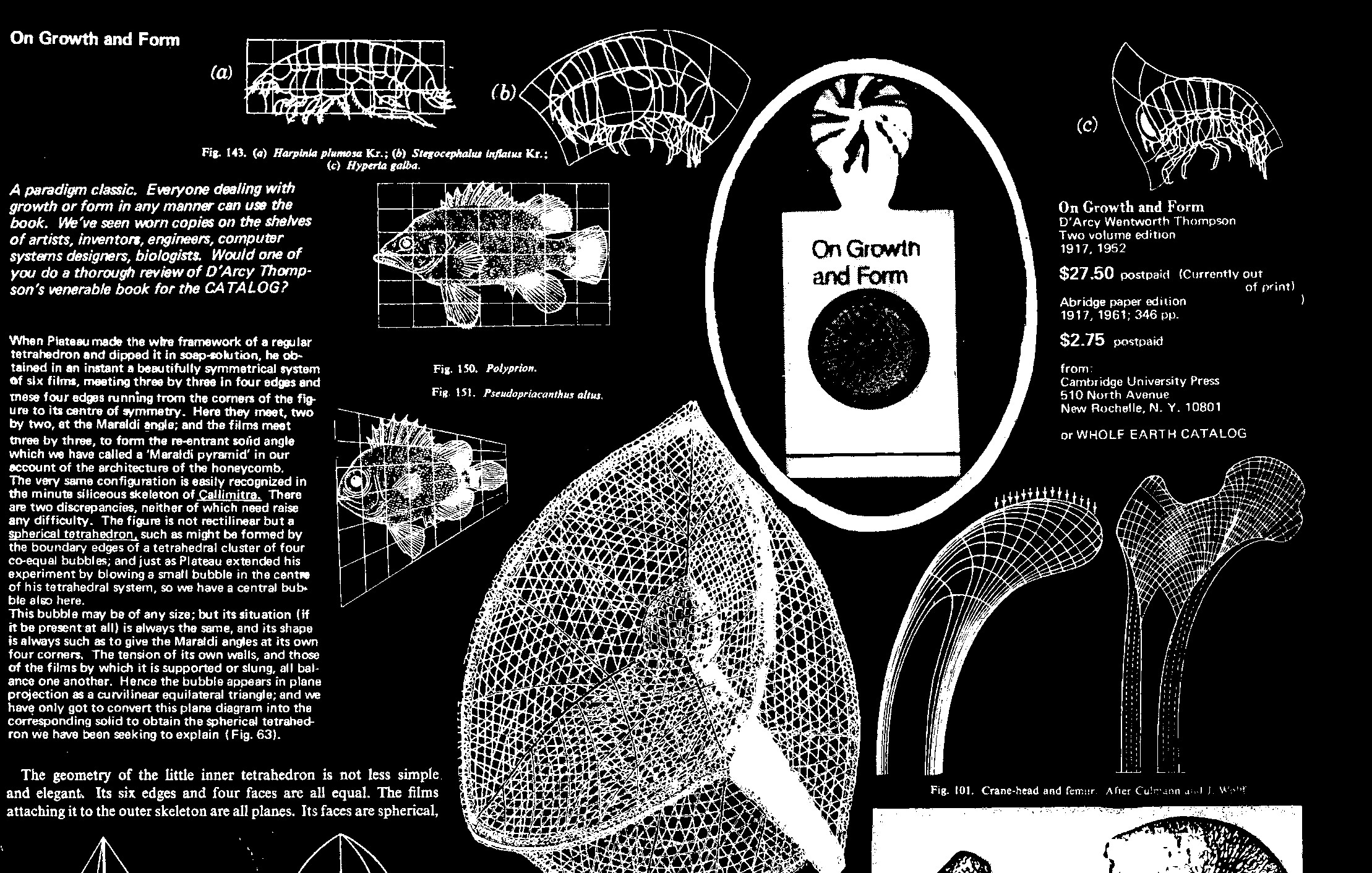

WEC similarly has a lot of talk of “whole systems”, fancy mathematical diagrams, and Marshal McLuhan speak. Here’s a review from the second page that gives an idea of what I’m talking about:

This is not how a Quora writer in 2014 or a Substack author in 2024 would write, but it engages in a sort of intoxicating “bigness” that both platforms frolic(ed) in. The “importance” of the ideas blinds the author to the ridiculousness of what they’re talking about. The result is science-fiction-resembling writing without all the philosophical and conceptual exploration of actual science fiction. I have no idea if the actual book is like this, but the quotes, hand-picked to feel like a succession of punches in the stomach, don’t inspire much confidence in me.

It’s not necessarily a bad thing to grope towards “importance”, directed only by vague feelings. This is what people do every day of the week. This is how I’ve come upon every big decision I’ve ever made in life. They’re also quite honest about it, like in this review of Needham’s Science and Civilization in China, where they admit they haven’t actually read it:

I'm of course no stranger to the production of fake deepness. English language discussions of Chinese lend themselves quite well to fake-deep statements, since it can take years and years to have any real familiarity with the language, but there are also a lot of people who are casually curious about it. After studying Chinese for a year, I'd probably thought about it more than I'd thought about anything else up to that point -- it seemed obvious to me that I must have great insight about the nature of the language. I didn't yet have the context necessary to understand what it's like to study something that is truly deep. It takes multiple years just to be conversant, and it's necessary to first be conversant before you can be exposed to a great quantity of the language. Before such exposure, it's possible to come up with all sorts of ridiculous theories based on a single sentence or a pattern exhibited by two or three words. Even worse, without actually using the language on an everyday basis, it's so easy to exotify it, mystify it, turn it into fuel for philosophical speculation rather than just another medium for communication, no different from English.

The main issue, I think, is that "fake-deep" is a matter of framing. A lot of the kind of "big idea shallow thinking" that I'm talking about is simply a result of people trying to understand something by putting their thoughts into writing (often for the first time wrt this particular topic). When it's done in private, or at least clearly labelled as "thinking aloud", there's nothing wrong with this. The nature of Quora as a platform for answers however messes up this dynamic. There's a false authority given to random stranger's attempts at thought, especially when they happen to get large amounts of upvotes, awarded to them by other people who have no idea what they're talking about.

So this gets into one of the central issues I face as "a guy with a website".

I have a middling amount of knowledge about a lot of topics that many people (or at least certain sorts of people) are curious about, but which have a reputation for being difficult and unapproachable. Part of why I turned out like this was that I was tricked by people on the internet alluding to knowledge they didn't actually have. I wanted to be like those people, and placed way too much trust in them. Of course, this isn't really their fault. I tend to be a rather delusional individual. If someone quotes Ovid, I instinctually assume they've read the entire Metamorphoses in the original Latin. This, it turns out, is not a very good assumption. Yet, in talking to people who take me to be a little more educated than I actually am, I've found these sorts of assumptions aren't unique to me.

My biggest nightmare is pretending to false wisdom. I want to write about all the things I'm thinking about, which necessarily entails writing about things I don't really understand, but have slightly more knowledge about than my average audience member. I'm therefore very worried about misleading people.

This is one of the reasons why I don't write about actual things beyond my own life very much anymore. When I started this website I imagined myself as blossoming into a personality on the other side of the internet, writing about all the problems of our day from a completely original perspective, and I figured the way to start doing that was writing about things I found interesting, like Gong Gong Gong or New Pants. I thought those essays turned out pretty weak and forced, so I eventually gave up on them and instead turned my focus to my daily life and all my various forms of micro-sadnesses. I actually think this sort of writing is a lot more interesting than what I did before -- but it's also very limited in scope. I go back and forth between wanting to be content with my tiny little world, and wanting to push my writing forward, to think deeply about problems outside of myself and manage to say something meaningful.

This is where I admire WEC -- it suggests massive world changing ambitions, but it's also very fun and silly.

I keep convincing myself that I used to be funny, but I don't actually have any evidence. Whenever I go looking for my old "funny" writing, I can't actually find anything. It seems I've always been a gloomy and melancholic individual. Not that there can't be humor in that. Natsume Sōseki, whose world of words I've managed to fall in love with this year, was also a very gloomy writer that managed to be quite funny in even his most serious works, like The Gate or Grass by the Wayside. Though I have my doubts that I can ever write something remotely like Sōseki.

More than anything else, there is something wonderful about being bombarded by many kinds of books that I didn’t know existed. There’s a certain standard to the WEC that goes far beyond anything I’d been recommended on Quora. It’s not just that it presents the possibility of, say, learning to make my own documentaries or learning how to draw by imagining the tactile feel of objects — the most wonderful aspect is that it bears testament that this particular topic can be written about in a special and unique way, so now I know to look out for other books that write about other topics in similar ways.

It’s not unlike going to the Tsutaya bookstore down the street from my house and each time discovering a new “format” of book, for instance pocket sized books with full color prints of 19th century Japanese paintings of devils and villains. I can imagine myself for a moment standing on the subway, leaning against the wall and holding this tiny book open with one hand, flipping through and immersing myself in a world of blood covered heroes and long necked demons as I get pulled forward through the darkness outside the subway window.

Perhaps self-education should not be governed by any particular philosophy. Just stumbling upon something new and finding oneself involuntarily reaching forward towards that which, for whatever inexplicable reason, has a greater gravitational pull than everything else around it — isn’t that enough? Education necessarily involves learning what you don’t already know. To have a philosophy around it means making assumptions about those unknowns, which I worry is too restrictive.

Books and books —

my room is filled with

stacks of books.

I need to pee, but

books block the door.